Global pandemic CoVid-19 has affected to our daily life for almost a year so far. Many of us work mostly remotely, my last visit to campus was in August 2020. This situation will probably go on for several months. At the beginning of February 2021, we got news that we in LAB University of Applied Sciences will continue in remote education and working mode for the spring semester 2021. The motivation for this article is to present and discuss innovation-related competencies, how they could be fostered, and why we all should give a thought on the subject.

Author: Pasi Juvonen

Introduction

The article is organized as follows: First, competencies needed to generate innovative ideas are presented and actions to foster them is discussed. Secondly, different paradigms about innovation process is presented. Third, some observations on how we in LAB could benefit from these data are presented and discussed. Finally, a short summary about the subject is made.

Innovation is a popular topic for study

Innovation-related themes have been studied for a long time. It has also been claimed that due the popularity of the subject, innovation-related topics are passe. To get a picture about the popularity of the subject two simple tests were made.

- Amazon, a huge and well-known bookstore returns over 60 000 items with search string “innovation” (searched 1/2021). When specifying search to “innovation process” there is still 266 books in results, and “innovative skills” returned 22 results respectively.

- The same search strings were repeated with google and google scholar (focused on academic knowledge) search engines with the following results: “innovation” 812 000 000 / 4 100 000 results, “innovation process” 2 550 000 / 455 000 results, “innovative skills” 685 000 / 9670 results.

Based on these data it seems evident that we sure know a lot about the subject. The amount of data is already so huge that an artificial intelligence can write a book about innovation. At the same time 94% of CEOs are not satisfied how their organization innovate (Rehn 2019). In what kind of situation are we in LAB? How much have we employed this information into practice and turned it into knowledge? What are the 2-3 specific habits we have changed in our daily routines based on the information we have gained about innovation-related themes? This article discusses these questions.

How to foster abilities for creating innovative ideas?

In 2020’s we have a huge set of information, models, methods, and tools (web resources) all the time available for us to support our actions. Strengthening our personal knowledge base is much easier compared to times when web did not have much content to offer, beginning of 1990’s.

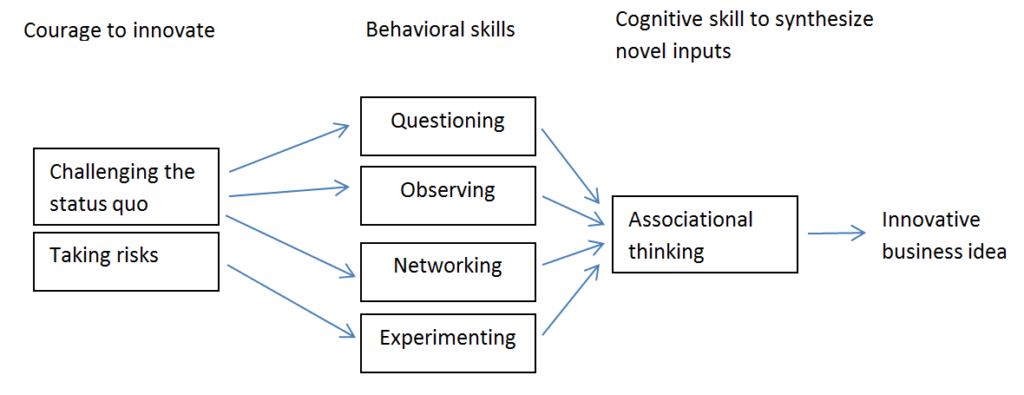

So, we have lot of information available for those who are interested to learn more. With appropriate mix of attitude, curiosity and utilizing possibility, innovative thinking will be fostered. A framework of competencies needed in generation of innovative ideas is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Innovators DNA – competencies needed in generating innovative ideas (Dyer et al. 2011)

The skills presented in Figure 1 are so-called discovery-driven skills. They differ remarkably from delivery-driven skills (analyzing, designing, detail-level implementation and obedience). Every organization needs a balance between these two skill sets. These discovery-driven skills are shortly presented next.

First, we can usually recognize natural innovators from their habit to actively challenging the status quo and – what is important – suggesting how it could be changed. This has sometimes been called a creative tension and it pulls innovative minds to act. Innovators are ready to take risks. Even though is always at least risk of failure when trying something new, natural innovators are more worried about where we might end up without taking those actions.

Innovators ask a lot of questions, and those questions are in many cases ones that others have not asked. The innovators emphasize good questions over good answers. The innovators challenge the status quo with questions such as “What if?” “Could it be both and rather than either or?” “Why?” “Why not?” The innovators participate in different events, build networks by inspiring others, asking questions, and testing their own ideas in different contexts. The innovators are keen to network with a person with different knowledge than their own to be able to complement their own view with fresh viewpoints. The innovators are not interested whether they are popular among others or not. They rather focus on the target and if it requires to be unpopular, they will accept the role.

We all look, but only few of us observe. The objective of observation is to recognize hidden needs, which cannot be revealed when using surveys and / or theme-based interviews. Targets of observation include people’s behavior, processes, use of products and companies and their way of organizing operations. Innovators are keen to understand how these phenomena take place in their natural environment. The innovators will not easily accept explanations that are too obvious or seem too easy. They are willing to ask 5 times why to dog into root causes of issues. This will require time for dialogue, and if we are in a hurry all the time, the time is not given to discuss root causes more deeply. So, we end up nurturing symptoms rather then curing the decease.

Innovators gain new experiences all the time by piloting ideas and by making prototypes. The prototypes will be tested with limited number of users or in a limited geographical area. The experiments are made to test how ideas will work in practice. Innovators prefer “cheap and nasty” experiments because they give a possibility to make more experiments – and more you experiment, more you learn. Best innovators are especially good in experimenting. The experimenting skill is closely connected to reflection and learning (build – measure –learn… and repeat). Experimenting does not always require physical proof of concept (PoC) or minimum viable product (MVP). It is also important to experiment new ideas with colleagues to gain feedback and new insights. In specialist organizations we tend to develop ideas alone and present them when they are more “ready”. Though this prevents embarrassment of presenting incomplete results, it will at the same time make it more challenging for colleagues to participate and commit to. New ideas should be presented to at least one colleague as soon as possible. The idea will be tested and sometimes also rejected, either way it is a rapid test of it.

Association means surprising connections (flashes of insight) between different ideas, knowledge domains, technologies, concepts, products, services or business domains. Creating associations usually requires a broad view based on a long period and enough time to reflect different connections between issues. A fruitful situation for association exists when a person has a lot of knowledge in one problem domain but also some knowledge from other problem domains. This helps in conversations with the experts of other problem domains. To better enable this, we could have more dialogues where specialists with different background can interact. When creating new, hurry is the worse enemy of creativity.

As for an individual innovator, cognitive and behavior skills are rarely on an equal level. However, an innovator has usually strong competence in one or two of the skills mentioned above. In addition, the other skills are also at least on a good level. In teams, it is crucial that there will be supplementing skills (Dyer et al. 2011). When building working groups – that may later become teams if nurtured properly – an important issue is to start with “a plant”, a person who is able to generate ideas and the finding a leader who can get along with this plant (Belbin 2003). Belbin (2003) emphasizes the role of the plant in working groups. Because the plant is usually not much interested in routines there should also be at least one coordinator who is interested to documents the concept level of tasks at hand and at least one finisher who eagerly takes care that given tasks will be finished in detailed in a given time. (Belbin 2003)

Based on Moore (1991) only 2.5% of individuals are natural innovators. Despite of their small number, their role in spreading new innovations is remarkable. Even though the innovators are in many cases not able to communicate in a way majority would understand them, they will attract early adapters and present innovations to them. When early adapters know the benefits of the innovation and how to use it, they will present the innovation to an early majority. The early majority will then affect to late majority. Moore (1991) calls this the first chasm of demand. Though the Moore’s model is seasoned it still seems to be used also as part of technology acceptance and market entry plans.

Paradigms concerning innovations and their comparison

Denning and Dunham (2010) suggest that preconditions for a successful innovation are: 1) domain knowledge, 2) an ability to see opportunities (positive attitude), and 3) an ability to influence to other people. Best preconditions for successful innovations appear in the intersection of these three skills.

Sometimes a specialist culture may lead into situations where colleagues, superiors, and subordinates are protected from the truth, because it is thought that the truth is too hard to handle (Kets de Vries 2011; Aaltonen 2010). These phenomena prohibit the circumstances for real multi-disciplined work and inhibit the possibilities to create fruitful preconditions for boundary innovations (Johansson 2005), where expertise from multiple areas is connected creating something radically new. Nowadays we live in times of uncertainty, which means that we cannot know beforehand whose expertise will be needed to solve the future challenges. Therefore, it is important to build teams with different types of expertise (Katzenbach & Smith 2001; Furr & Dyer 2014).

Team building always starts from getting to know each other and spending time together and by that means building trust. These work best face-to-face but because this option has not much been available for a while, be should consider how to organize spending time together and building trust with each other via digital tools also. Though digital tools in theory make us equal participants in Teams or Zoom, in practice we have quite different communication and dialogue culture in different domains of education.

Based on Denning and Dunham (2010) there are four paradigms concerning innovations: mystical, process, leadership and generative. The mystical paradigm includes thoughts about special abilities, genes, luck, serendipity and even magic. The process paradigm sees innovation as a set of manageable processes with pre-definable results, behaviors, and transitions rules from stage to another. The leadership paradigm claims that a leader or manager creates the innovation strategy and innovation culture and then persuades employees to adapt into new practices. Based on the generative paradigm innovations are results of interaction between individuals. The interaction consists of listening, articulating benefits, observation, and committing to conversations based on which effective actions are taken to employ new practices (Denning & Dunham 2010).

Denning and Dunham (2010) also present strong criticism against the leadership paradigm. Real life is not so easy. Communication problems between people, politics and bargaining, lack of knowledge and knowledge hiding, solo playing, solidarity, trust or lack of it, commitment or lack of it and resistance for change are not part of the leadership paradigm. However, they are part of daily innovation work. Furthermore, depending on whether a leader sets a framework (problem domain) for employees’ work or not, a different baseline for innovations is created. When someone else sets the framework (conventional approach) we usually get results, which are inside the framework that has been set. This can be described as single-loop learning (Argyris & Schön 1996). On the other hand, when the framework for the innovation does not exist or is too broad, the individuals may perceive the situation as lack of competence or organized behavior. To avoid extra frustration, it is good to describe co-workers the background, based on what decisions have been made concerning the innovation framework.

To active double-loop learning (Argyris & Schön 1996) where individuals are encouraged to question their earlier assumptions and beliefs to be able to learn more deeply and update their assumptions and beliefs, we need different kinds of appointments. In some cases where we are familiar with the expectations and the problem domain, a tight appointment with active chairperson is a good choice. In situations where problem domain is newer to everyone or has not been formed yet, we need more open agenda and circumstances where incomplete thoughts and ideas can be articulated.

Observations on building an innovation culture

Innovation management should be approached with a toolkit where all four previously mentioned paradigms are balanced. None of the four paradigms should be overemphasized. Denning and Dunham (2010) also argue that analytic processes are often over-emphasized in innovation and management. This will draw attention away from interaction, building trust, influencing others and to be influenced, intuition, presence, negotiation, building support and diminishing resistance to change. In other words, we often try to control issues that in real life cannot be controlled.

When building Innovation culture, we should focus on creating conditions for actions. We should also measure idea input, throughput, and output as Hamel and Green (2012) suggest. When something is seen as important, there should be resources to foster subjects’ further development. Furthermore, when there are resources available, we can also expect delivery of results with the subject. From another viewpoint, if some tasks are not well resourced, employees easily feel that they are not important. Saying: “Put your money where your mouth is” is true here.

This set objectives and attach resources to achieve will foster culture of discipline to develop (Collins 2001). This means that we will support development of organizational culture where we will not tolerate underperforming and in the same time, we will not allow overperforming or overconsumption of human resources.

Steps towards deep innovations culture

Rehn (2019) points out what we should emphasize when creating deep innovation culture. It consists of 4 R’s that can be summarized as follows:

- Respect – lead by example. Focus on details and recognize and reward desirable behavior. Spread good experiences and accept disagreement. Respect the knowledge of others.

- Reciprocity – when objectives are raised, offer tools and resources to achieve them. Gather continuous feedback of how change is proceeding.

- Responsibility – Focus on meaning and purpose. Make intervention when you recognize indifference. If you recognize lip service, refocus it to solution-oriented dialogue.

- Reflection – allow and foster open dialogue including justified critique. Challenge status quo and shallow culture. Continuously develop interaction skills. Courage to show one’s own vulnerability.

To achieve the above, it all starts of more and better dialogue. The Covid-19 pandemic has moved us to remote work settings. In theory we are now more able to choose from where we work and participate. Based on my observations, it seems that many of us is more overloaded than ever. Most of us change from meeting to other in a minute, sometimes without any physical pause and possibility to our brain to rest and reorientate. Hurry and hustle accumulate, and we easily end up to act in an autopilot mode just performing our daily tasks. This might be okay for some routine tasks but not all our tasks are routine. We all should have time to think, question, criticize and sometimes challenge the status quo. Unfortunately, in hurry we are not able to make exact observations of where we are, where should be going, and how could we get there (Ahonen 2004; Hakala 2013).

Having a dialogue has often been criticized taking much time in situations where we do not have time. My answer has been and still is that usually via learning better dialogue we will be able to better catching the root causes of why we have hurry and haste in first place. If the dialogue ends to a flash of insight about how to reorganize our daily work to better avoid hurry, it pays back the time used to it with multiple of huge number. Naturally we need practice to be able to communicate our situation openly and genuinely and admitting that showing one’s vulnerability is rather a strength than a weakness. William Isaacs, one of most famous researchers of dialogue and co-founder of MIT’s Sloan School of Management, has argued that companies that have chosen to emphasize dialogue to better their communication culture and lessen their hurry have not regretted their choice (Isaacs 1993; 1999).

In situations where events, confusion of opinions or chaos challenge our assumptions, beliefs, and mental models, we tend to stick even tighter to our secure thoughts and previous expertise (Denning & Dunham 2010). In those situations, it will be extremely hard to find mutual benefits. People easily end up in debate and lose purpose. In the worst case, everyone loses, and the results will be negligible. Focus should be turned into asking open ended questions and reflective reframing (Hardagon & Bechky 2006), finding root causes and developing solutions for solving them together. This will create psychological safety (Schein 2004) which will enable cooperation and lessen the enemies of innovation that are fear and doubt (Brien 2018).

Ideally, in every dialogue, there should be at least one facilitator or coach who is familiar with the basic rules of dialogue: speak from your heart, respect, listen, and suspend to make judgments too soon (Isaacs 1999) and the phenomena of the group dynamics (Levi 2007) present. The facilitator will help participants to move from debate to productive discussion and dialogue by balancing the flow of interaction. Normal discussion will not develop into genuine dialogue without understanding the basic behavioral rules of dialogue. The genuine dialogue usually seems much easier than it is and this in many cases inhibits experienced specialists from learning it. It may be challenging to admit that there is room for development both in one’s own knowledge and methods of interacting. And without admitting it to yourself and asking feedback from others about your communicative style, improvements are unlikely.

Discussion

In LAB we are in situation where objectives for RDI growth have been set high – to almost triple external RDI funding by 2026. The objective has been communicated to us and we are doing our best to express what resources will be needed to attain the objectives. It is inevitable that we need to find new sources for external funding from nationally competed funding, international funding, and direct funding from companies. This all requires development of new skills. It can partly be achieved via development the know-how of our current personnel. In addition, we need plenty of experienced RDI -focused specialists. And we need to start preparing recruiting them quickly to be able to utilize their know-how in building new consortiums for national and international RDI projects.

Cultural change as any change is led by example. Therefore, we need open dialogue in every level to better understand where we are now, what good practices we already have, where are the places for improvement, and what are the areas where we need to develop our know-how. In some stages we also must also steer our thoughts from asking why and start discussing questions of how and what. Having open and genuine dialogue of these issues is not always easy but we do not have any other choice. Via open and genuine dialogue, we can build trust and commitment. The trust and commitment are needed when learning new things to keep fear and doubt away.

References

Aaltonen, M. 2010. Robustness. Anticipatory and adaptive human systems. Litchfield Park: Emergent publications.

Ahonen, H. 2004. Kuka komentaa kelloasi. Helsinki: Kirjapaja.

Argyris, C. & Schön, D. 1996 Organizational learning II: Theory, method and practice. Reading: Addison Wesley.

Belbin, R. M. 2003. Team Roles at Work. Oxford: Elsevier.

Brien, N. 2018. The Rise of the Conscious Organization. The Fifth Industrial Revolution. Stanstead: Rise Humani-T Publishing.

Collins, J. 2001. From Good to Great. Why some Companies make the Leap and others don’t. New York: Harper Business.

Denning, P.J. & Dunham, R. 2010. The Innovators Way. Essential practices for successful Innovation. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Dyer, J., Gregersen, H. & Christensen, C.L. 2011. The Innovator’s DNA. Mastering the five skills of disruptive innovators. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Furr, J. & Dyer, J. 2014. The Innovator´s Method. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Hakala, J. T. 2013. Luova laiskuus. Anna ideoille siivet. Helsinki: Gummerus.

Hamel, G. & Green B. 2012. What Matters Now. How to win in a World of Relentless Change, Ferocious Competition, and Unstoppable Innovation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hardagon, A. B. & Bechky, B. 2006. When collection of Creatives Become Creative Collectives: A Field Study of Problem Solving at Work. Organization Science. Vol. 17 (4), 484 – 500. [Cited 2.2.2021] Available: https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0200

Isaacs, W. 1993. Taking flight: dialogue, collective thinking and organizational learning, Organizational Dynamics. Vol 22 (2), 24-40. [Cited 2.2.2021]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(93)90051-2

Isaacs, W. 1999. Dialogue: The art of thinking together. New York: Currency.

Johansson, F. 2005. Medici-ilmiö. Huippuoivalluksia alojen välimaastoissa. Helsinki: Talentum.

Katzenbach, J.R. & Smith, D. K. 2001. The Discipline of Teams. A Mindbook-Workbook for Delivering Small Group Performance. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Kets de Vries, M.F.R. 2011. The Hedgehog Effect. The Secrets of Building High Performance Teams. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Levi, D. 2007. Group Dynamics for teams, 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Moore, G. 1991. Crossing the Chasm. Marketing and selling High-Tech Products to Mainstream Customers. New York: Harper Business.

Rehn, A. 2019. Innovation for the fatigued. How to Build a Culture of Deep Creativity. London: Kogan Page.

Schein, E.H. 2004. Organizational Culture and Leadership. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Author

Pasi Juvonen is the RDI Director of Commercialization of Innovations at the LAB University of Applied Sciences.

Illustration: https://pxhere.com/fi/photo/1436407 (CC0)

Published 12.3.2021

Reference to this article

Juvonen, P. 2021. How to foster our innovation-related skills? LAB RDI Journal. [Cited and date of citation]. Available at: https://www.labopen.fi/en/lab-rdi-journal/how-to-foster-our-innovation-related-skills/