The recreational value of nature is undeniable. The increasing popularity of nature travel is affected also by increased awareness of the impacts of nature on our well-being. This article discusses well-being effects of nature, in particular, forests and how everyone could benefit from these effects. It also showcases the concept and some applications of Health Forest model.

Author: Tuuli Mirola

There is a growing interest in understanding the role forests play in human health. Numerous contributing effects on health and well-being but also negative impacts due to deforestation and forest degradation have been identified. (WWF 2022, 5) Some effects are direct, some undirect. Forests enhance well-being through provisioning, preventative, and healing functions (WWF 2022, 13).

Exposure to forests contributes to social, psychological and physical well-being (Tapaninen 2022). However, the relationships between individuals and forests are strongly influenced by their life experiences, health conditions, social needs and demands, access and accessibility to forests, forest proximity and the affordability of a person’s exposure to forests (WWF 2022, 13).

Access to forests enhances physical activity (Tyrväinen et al. 2018, 1387). Mental wellbeing, relaxation and getting away from noise and pollution, are among the factors motivating nature park visitors (Tapaninen 2022). Studies have identified a wide range of benefits, including improving immune system, potentially increasing resistance to cancer, decreasing blood pressure, stress and anxiety and serum cortisol levels, increasing relaxed feelings and lowering heart rates and levels of blood glucose (WWF 2022, 19-20).

Image 1. Contact with forest soil can boost immune system (Perjensen 2017)

Forests have also potential in public health promotion and disease prevention. (Tyrväinen et al. 2018, 1387) Health Forest is a pioneering Finnish operating model that systematically utilizes the scientifically proven health benefits of nature as a part of the official health care system. (Health Forest 2020) The health-supporting method, in which patients of healthcare centers are taken to guided forest treks as a part of their treatment, has been used since 2015. The model has been further expanded for work communities, elderly, young people, children, and rehabilitation. (Terveysmetsä 2020a) The results have been positive with increased well-being consistently reported by the participants. (Health Forest 2020)

In Japan, there are dozens of certified health forests (Metso 2015). Numerous research on forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku), immersing oneself in nature using one’s senses, has examined the mental health impacts of forests (Kotera et al. 2020). Improvements have been described in mood disorders, stress, mental relaxation and depression. Forest bathing can regulate emotions, through soothing and calming. (Kotera et al. 2020, 338).

How could the health benefits of forests be provided to everyone?

Increasing number of nature travel destinations and services enable more and more people to enjoy nature and its well-being impact. For example, the number of visitors in national parks has shown an increasing trend in the recent decades (Konu et al. 2021, 10). Well-being travel is one of the fastest growing areas of international travelling (Renfors 2021).

Land use planning and development projects of municipalities play a key role. Creating forests in urban areas provide recreational benefits as well as positive health effects. Urban forests, parks and nature paths offer citizens with easily accessible opportunities even without travelling. Getting into touch with nature on our everyday activities is essential, for example, in order to benefit from the forest microbes (THL 2019).

One example of these kinds of urban forest development projects is the Health Forest concept created in Finland. Geographer Marko Leppänen and biologist Adela Pajunen (2017) have seeked to find out what kind of nature destinations, natural elements and landscapes have a particularly positive effect on people. They have systematically explored different locational characteristics of revitalizing nature environments. Their book “Terveysmetsä” features details of 31 qualities for a Health Forest (Leppänen & Pajunen 2017). Some Health Forest qualities are primary characteristics of the forest, such as a high level of biodiversity. Other qualities are secondary and derived from proper planning. These include e.g. accessibility, structures and services. (Health Forest 2020)

The first Health Forest path was created in Vartiosaari, in Helsinki in 2013 (Terveysmetsä 2020b). The effects of this path 2,5 km long have been investigated by surveying the experiences of test visitors. The initial results indicated clear enhancement in perceived and measured well-being. For example, blood pressure decreased, and relief of stress and worries increased. (Sitra 2017, 4)

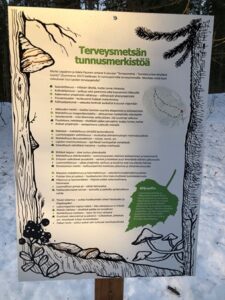

Lappeenranta got its own 1 km long Health Forest path in Uus-Lavola in 2021 (Lappeenranta events 2021). The info boards along the path present well-being and health effects of nature and challenge the visitors to find out how many of the 31 criteria set out for Health Forests they can experience during the visit. For example, is it possible to enjoy the silence and sounds of the forest, to contact animals, to pick berries or mushrooms, to get into touch with the soil, or to experience water elements?

Image 2. Info board on Health Forest path in Uus-Lavola (Image: Tuuli Mirola)

However, even though there are plenty of options, not everyone visits or even has any access to forests. Finns are spending over 90% of time indoors and more often in urban environment (THL 2019). Therefore, numerous projects and research has been done to find out, how the benefits of forests can be brought to the urban environment, even indoors to homes and offices.

For example, the idea of creating more versatile microbiota indoors has been tested by bringing carpets treated with forest soil to homes. (THL 2022). In another example, adults rubbed forest soil-based powder on their hands daily for 2 weeks. The results showed increase in body’s microbiological diversity. Further research is needed to test if more diverse microbiota can be used to prevent immune-mediated diseases. (Vierula 2018)

The Virtunature project examined the benefits of virtually produced natural environments for stress relief in an office environment. Volunteers visited a Virtual Nature Room during their afternoon work breaks. Volunteers either watched a forest or a water environment video on a TV-monitor with related nature sounds, they listened nature sounds (without a video), or were sitting in the quiet room without exposure to any audiovisual material. The stress level was lowest during viewing the forest landscape video. Viewing nature videos was found to be more restorative than sitting in the silent room. (Ojala et al. 2019, 5)

Nature experiences can be produced indoors with advanced digital technologies (Ojala et al. 2019, 5) but even watching photos of nature can enhance mood and reduce tension and anxiety (Sitra 2013, 15). Thus, anyone can benefit from these well-being effects of forest.

The well-being effects of nature have been investigated on Project Kurenniemi – Cultural value of Russia and Finland through M. Agricola trail within the framework of South-East Finland – Russia CBC Programme 2014–2020.

References

Health Forest. 2020. Cited 4 Feb 2022. Available at https://terveysmetsa.fi/healthforest/

Konu H., Neuvonen M., Mikkola J., Kajala L., Tapaninen M. & Tyrväinen L. 2021. Suomen kansallispuistojen virkistyskäyttö 2000–2019. Metsähallituksen luonnonsuojelujulkaisuja. Sarja A 236. Cited 26 Jan 2022. Available at https://julkaisut.metsa.fi/assets/pdf/lp/Asarja/a236.pdf

Kotera, Y., Richardson, M. & Sheffield, D. 2022. Effects of Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy on Mental Health: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. Vol. 20(1), 337–361. Cited 1 Apr 2022. Available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00363-4

Lappeenranta events. 2021. Uus-Lavolan terveyspolun avajaiset. Cited 4 Apr 2022. Available at https://tapahtumat.lappeenranta.fi/en-FI/page/619c9297c1eb0038fffda1dd

Leppänen, M. & Pajunen, A. 2017. Terveysmetsä: Tunnista ja koe elvyttävä luonto. Helsinki: Gummerus.

Metso. 2015. Kolme suomalaista mallia terveysmetsäksi. Cited 4 Apr 2022. Available at https://www.metsonpolku.fi/fi-fi/ajankohtaista/kolme_suomalaista_mallia_terveysmetsaksi

Ojala, A., Neuvonen, M., Leinikka, M., Huotilainen, M., Yli-Viikari, A. & Tyrväinen, L. 2019. Virtuaaliluontoympäristöt työhyvinvoinnin voimavarana: Virtunature-tutkimushankkeen loppuraportti. Luonnonvara- ja biotalouden tutkimus 51/2019. Helsinki: Luonnonvarakeskus. Cited 4 Apr 2022. Available at http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-326-799-2

Perjensen. 2017. Puolukka Syötävä Metsänpohja Pudota Suomi. Pixabay. Cited 4 Apr 2022. Available at https://pixabay.com/fi/photos/puolukka-sy%c3%b6t%c3%a4v%c3%a4-mets%c3%a4npohja-pudota-2904679/

Renfors, L. 2021. Hyvinvointimatkailu on yksi kansainvälisen matkailun nopeimmin kasvavista osa-alueista. Business Finland. Cited 17 Mar 2022. Available at https://www.businessfinland.fi/suomalaisille-asiakkaille/palvelut/matkailun-edistaminen/tuotekehitys-ja-teemat/hyvinvointimatkailu

Sitra. 2017. Terveyspolku Helsingin Vartiosaaressa. Cited 4 Apr 2022. Available at https://media.sitra.fi/2017/02/27174401/Terveysluontopolku_esite-2.pdf

Sitra. 2013. Vihreää hyvinvointia. Cited 4 Apr 2022. Available at https://media.sitra.fi/2017/02/27174340/Vihreaa_hyvinvointia-2.pdf

Tapaninen, M. 2022. Nature activities and travel trends in the national parks of Finland. Presentation in Wellness from nature experiences -webinar on 2 Feb 2022.

Terveysmetsä. 2020a. Mikä on Terveysmetsä? Cited 4 Apr 2022. Available at https://terveysmetsa.fi/mika-on-terveysmetsa/

Terveysmetsä. 2020b. Terveysmetsä-polku. Cited 4 Apr 2022. Available at https://terveysmetsa.fi/terveysmetsapolut/

THL. 2019. Microbiota in home indoor air may protect children from asthma – how to bring protecting microbiota into children’s everyday lives? Cited 29 Mar 2022. Available at https://thl.fi/en/web/thlfi-en/-/microbiota-in-home-indoor-air-may-protect-children-from-asthma-how-to-bring-protecting-microbiota-into-children-s-everyday-lives-

THL. 2022. Towards a health promoting indoor microbiome (The PROBIOM consortium). Cited 29 Mar 2022. Available at https://thl.fi/fi/tutkimus-ja-kehittaminen/tutkimukset-ja-hankkeet/towards-a-health-promoting-indoor-microbiome-the-probiom-consortium-

Tyrväinen, L., Lanki, T., Sipilä, R. & Komulainen, J. 2018. Mitä tiedetään metsän terveyshyödyistä? Lääketieteellinen Aikakauskirja Duodecim. Vol. 134 (13), 1397-1403. Cited 29 Mar 2022. Available at https://www.duodecimlehti.fi/xmedia/duo/duo14421.pdf

Vierula, H. 2018. Kädet likaantuvat mutta mieli lepää. Lääkärilehti. Vol. 73 (32), 1640-1642. Cited 1 Apr 2022. Available at https://www.laakarilehti.fi/ajassa/ajankohtaista/kadet-likaantuvat-mutta-mieli-lepaa/

WWF. 2022. Vitality of forests: Illustrating the Evidence Connecting Forests and Human Health. Cited 1 Apr 2022. Available at https://files.worldwildlife.org/wwfcmsprod/files/Publication/file/94w0x82u61_FINAL_VoF_report.pdf?

Author

Tuuli Mirola, D.Sc. (Tech.), works as a Principal lecturer and she is the Project manager in the Kurenniemi – Cultural value of Russia and Finland through M. Agricola trail project.

Illustration: Tuuli Mirola

Published 19.4.2022

Reference to this article

Mirola, T. 2022. How can we benefit from the well-being effects of forests? LAB Pro. Cited and date of citation. Available at https://www.labopen.fi/lab-pro/how-can-we-benefit-from-the-well-being-effects-of-forests/