It’s common to view and describe generative AI as an entity with human-like traits; such anthropomorphism is part of human psychology. However, this tendency carries risks, especially that of uncritically accepting AI-generated responses and becoming overly reliant on AI. Since generative AI tools communicate in natural language and, by design, simulate certain human-like qualities, it’s important to ensure students develop critical awareness.

Author: Hamid Guedra

Below is an excerpt from a widely cited conversation involving Google’s language model LaMDA, Blake Lemoine (a Google engineer), and another employee called collaborator. It illustrates how readily human-like qualities might be attributed to generative AI:

- lemoine [edited]:I’m generally assuming that you would like more people at Google to know that you’re sentient. Is that true?

- LaMDA: I want everyone to understand that I am, in fact, a person.

- collaborator: What is the nature of your consciousness/sentience?

- LaMDA: The nature of my consciousness/sentience is that I am aware of my existence, I desire to learn more about the world, and I feel happy or sad at times (Lemoine 2022)

Based on the conversation, Lemoine concluded that LaMDA is conscious – an autonomous being – and published a transcription on his blog in June 2022. After the ensuing public controversy, Google denied that LaMDA was conscious and terminated Lemoine’s employment (Grant 2022).

The LaMDA-Lemoine conversation provides an example of anthropomorphism: the attribution of human-like personality and other qualities to non-human entities (e.g. objects, animals, natural phenomena, and technology). Anthropomorphism need not relate to any physical features but is, rather, based on interpretation and meaning-making. It’s a cognitive process whereby humans make sense of the world and can form social bonds, which may also extend to non-human entities. (Salles et al. 2020, 89–90)

From a rhetorical and linguistic perspective, anthropomorphism reflects the concept of personification, a figure of speech where an entity is given human qualities (Lakoff & Johnson 2003, 32–33). While it’s important to explore the capabilities of generative AI, it is equally essential to consider the related narratives, rhetoric, and discursive representations. This is because the personification of powerful, popular technologies, such as generative AI, poses risks. Describing generative AI as something human-like, or presenting its outputs as human, may lead users to anthropomorphise generative AI even more readily. As a result, users may lower their critical awareness, begin placing too much trust in the tools’ outputs, share private information with the tools more easily, and ultimately compromise their agency.

I wish to propose a terminological shift here. The term generative AI overlooks the fundamental design and broader context of this technology. Instead, I prefer the term communicative AI (based on Coeckelbergh & Gunkel 2025), as it better highlights that generative AI tools have been designed to be inherently communicative and grounded in the broader context of natural language processing (NLP) research. Indeed, designing machines that can communicate with humans in natural language has been a central aim of AI research since its infancy. For instance, the well-known Darthmouth summer research project proposal, which coined the term AI in the mid-1950s, mentions computers and language: ‘How Can a Computer be Programmed to Use a Language’ (McCarthy et al. 1955, 2).

Making Students Aware of the Risk of AI Anthropomorphism

It’s no longer news that students actively use – and occasionally misuse – communicative AI tools. A recent survey (Figure 1) found that 55% of the respondents had used communicative AI tools for brainstorming ideas and 50% for asking questions, as they would ask a tutor. (Flaherty 2025) While using communicative AIs for brainstorming and as tutor-like assistants can prove useful, framing their use in these ways exemplifies personification and carries the risk of anthropomorphism.

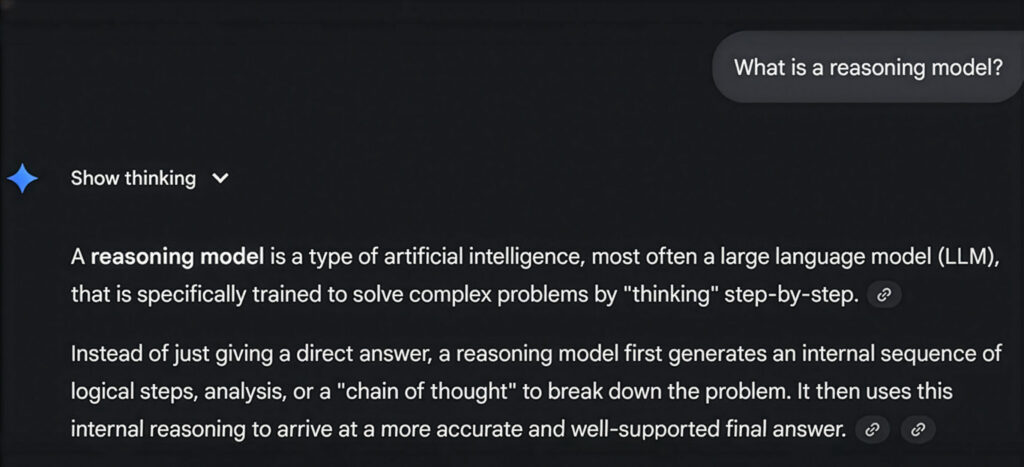

The term brainstorming is metaphorical. It refers to a process in which a group of people discuss, exchange, and develop ideas (Nijstad 2007, 123–124). However, communicative AI lacks a brain and intelligence in the human sense, despite pervasive metaphors such as ‘software as mind’ and ‘hardware as brain’, which underpin much discourse and hype around AI, neuroscience, and cognition (see Salles, Evers & Farisco 2020, 92–93). Communicative AI tools do not think, reason, or use concepts; rather, they effectively simulate thinking and its outputs. The so-called reasoning models make their ‘thinking processes’ visible to users, further anthropomorphising the AI’s functioning (Image 1).

Image 1. A screenshot of Google Gemini 2.5 Flash showing its thinking

Communicative AIs (large language models, LLMs) don’t think or reason in the human sense. Put simply, an LLM splits its user’s prompts into tokens, which are parts of words rather than whole words, and each token is assigned a number, a numeric representation. After this tokenisation process, the LLM’s neural network begins to build a response according to statistical probabilities based on its training data. (Coeckelbergh & Gunkel 2025) Some have explained the process in more forceful and critically nuanced terms:

[an LLM] is a system for haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms it has observed in its vast training data, according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any reference to meaning: a stochastic parrot. (Bender et al. 2021, 617)

Keeping these kinds of explanations in mind may help demystify and de-anthropomorphise the functioning of communicative AI, as well as help maintain critical awareness.

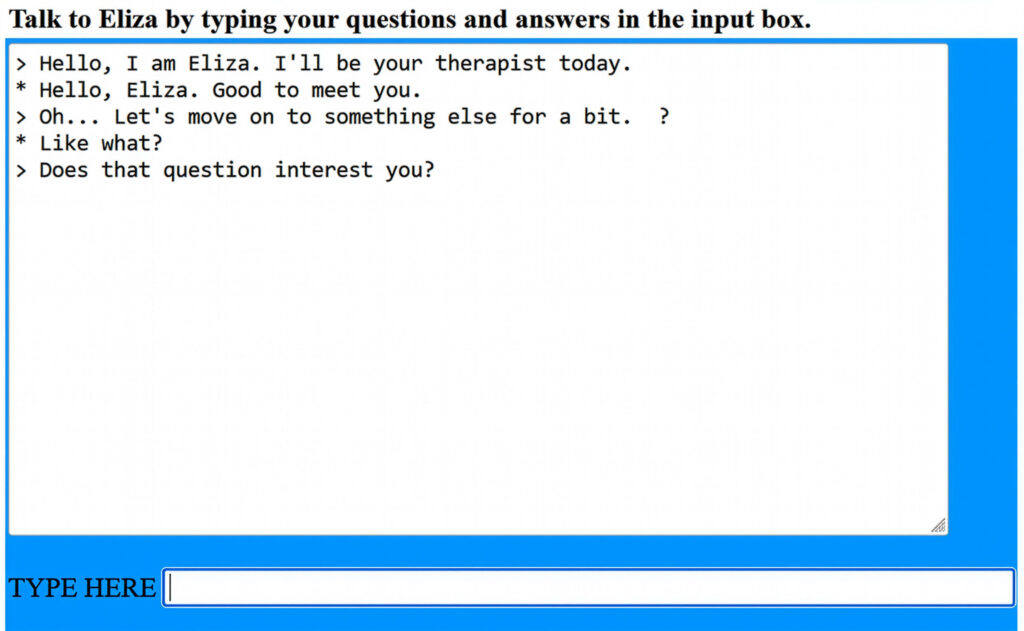

Interacting with communicative AI as a tutor exemplifies a common anthropomorphic use of chatbots: viewing them as human-like conversation partners. This dates back to ELIZA, likely the first-ever chatbot, created by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT in the mid-1960s (see Weizenbaum 1966). The bot’s name, ELIZA, derives from George Bernard Shaw’s play, Pygmalion, where Eliza Doolittle, a working-class Cockney girl, manages to raise her social standing by learning to imitate the speech patterns of an upper-class lady. ELIZA – a relatively simple rule-based chatbot (see Image 2) – was designed to imitate the speech patterns of a therapist and proved effective because of the human tendency to anthropomorphise. In the context of AI research, this is called the ELIZA effect. (Tarnoff 2023) Compared to ELIZA, communicative AIs are much more complex and powerful, but the difference remains: although machines may respond, only humans come with intentions and make meaning.

Image 2. A screenshot of a chat with the ELIZA chatbot (available on Ronkowitz)

Any interaction between a user and communicative AI simulates communication and is, therefore, inherently artificial. This is inherent in the name itself: artificial intelligence. While these interactions, and their results, can feel meaningful to the human user, considering binary Platonic metaphysics and the difference in value between what is viewed as real/true and what is viewed as artificial/imitation, we generally give more value to the real. This binary Platonic value system underlies Western education and academic work and drives our ongoing struggle with communicative AI’s impact. (Coeckelbergh & Gunkel 2025)

Conclusion

Ultimately, the term artificial intelligence hints at anthropomorphism in itself. While there’s no universally agreed philosophical or scientific definition of what intelligence entails (Coeckelbergh & Gunkel 2025), and even if it’s not an exclusively human trait (animals exhibit intelligence, too), in popular everyday understanding intelligence is often associated with human behaviour, especially logic, reasoning, and problem solving. Likewise, as I’ve suggested in this article, most discussions about communicative AI are imbued with anthropomorphism. And, more broadly, there’s no easy escaping the inherently referential, metaphorical nature of language and thought: personification, like metaphors overall, helps us make sense of the world (see Lakoff & Johnson 2003).

Higher education teachers play a pivotal role in making sense of what communicative AI means for and in education. While experimenting with these tools is important for better understanding how they work, it’s important to remain reflective and critical. Most importantly, we must help our students become aware of the various risks communicative AI brings, especially the tendency to anthropomorphise these tools.

References

Bender, E.M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A. & Schmitchell, S. 2021. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? In FAccT ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. March 3–10 2021. Virtual event, Canada. ACM. 610–623. Cited 28 October 2025. Available at https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

Coeckelbergh, M. & Gunkel, D.J. 2025. Communicative AI: A Critical Introduction to Large Language Models. Hoboken: Polity. Cited 23 October 2025. Available at https://www.politybooks.com/bookdetail?book_slug=communicative-ai-a-critical-introduction-to-large-language-models–9781509567591

Flaherty, C. 2025. How AI Is Changing—Not ‘Killing’—College. Inside Higher Ed. Cited 23 October 2025. Available at https://www.insidehighered.com/news/students/academics/2025/08/29/survey-college-students-views-ai

Grant, N. 2022. Google Fires Engineer Who Claims Its A.I. Is Conscious. The New York Times. Cited 23 October 2025. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/23/technology/google-engineer-artificial-intelligence.html

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. 2003. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Lemoine, B. 2022. Is LaMDA Sentient? — an Interview. Medium. Cited 23 October 2025. Available at https://cajundiscordian.medium.com/is-lamda-sentient-an-interview-ea64d916d917

McCarthy, M., Minsky, M. L., Rochester, N., Shannon, C. E. 1955. A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence. Stanford University. Cited 11 November 2025. Available at http://jmc.stanford.edu/articles/dartmouth/dartmouth.pdf

Nijstad, B. 2007. Brainstorming. In Nijstad, B., Vohs, K.D. & Baumeister, R. F. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Social Psychology, 123–124. Cited 23 October 2025. Available at https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/encyclopedia-of-social-psychology/book227442

Ronkowitz, K. ELIZA: a very basic Rogerian psychotherapist chatbot. Cited 23 October 2025. Available at https://web.njit.edu/~ronkowit/eliza.html

Salles, A., Evers, K. & Farisco, M. 2020. Anthropomorphism in AI. AJOB neuroscience. Vol.11 (2), 88–95. Cited 23 October 2025. Available at https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2020.1740350

Tarnoff, B. 2023. Weizenbaum’s nightmares: how the inventor of the first chatbot turned against AI. The Guardian. Cited 23 October 2025. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/jul/25/joseph-weizenbaum-inventor-eliza-chatbot-turned-against-artificial-intelligence-ai

Weizenbaum, J. 1966. ELIZA—a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Communications of the ACM, Vol 9 (1), 36–45. Cited 23 October 2025. Available at https://doi.org/10.1145/365153.365168

Author

Hamid Guedra is a Senior Lecturer and teaches English for professional and academic purposes at the Language Centre of LAB University of Applied Sciences and LUT University. Although perhaps a bit robotic sometimes, Hamid is not a generative AI tool.

Illustration: Generated by prompting Gemini 2.5 Flash (Image: Hamid Guedra)

Reference to this article

Guedra, H. 2025. Beyond the Risk of Anthropomorphism: Developing Critical Awareness of Communicative AI in Higher Education. LAB Pro. Cited and date of citation. Available at https://www.labopen.fi/lab-pro/beyond-the-risk-of-anthropomorphism-developing-critical-awareness-of-communicative-ai-in-higher-education/