This article discusses the importance of sustainable design and public procurement in reducing textile waste. The article refers to the Interreg Europe funded CECI – Citizen involvement in circular economy implementation project and the CECI Circular textiles survey, that was carried out in summer 2021. It is the second of the four articles concerning the textiles issue.

Authors: Barbora Pichlova, Antoine Delaunay-Belleville, Marjut Villanen & Katerina Medkova

Since the textiles industry is one of the largest ones in the world, nearly all countries are somehow involved in it. The involvement varies from the actual textile productions and transportation to product design, development of manufacturing technologies and consumption. The unsustainable textile production and use cause increasing problem of textile waste in all countries. (Speranskaya et al. 2018.)

Increased consumer sustainability awareness has been promoted among textile value chain including various textile industry representatives, governments and organizations supporting sustainability and circularity. Supporting sustainability and circularity transition calls for holistic approach with entirely novel and revolutionary ways of doing business, while considering economic, social and environmental benefits. (One Planet Network 2020.)

CECI – Citizen Involvement in Circular Economy Implementation is a Interreg Europe funded project, that gathers eight partners in six European regions. CECI aims to improve and to develop regional policies and strengthens citizens role. (Interreg Europe 2021a.) CECI collects good practices and exchanges knowledge between the project regions (Interreg Europe 2021b). In summer 2021, the CECI project partners conducted a thematic study and a workshop on circular textiles. Series of four articles will summarize the findings. The first article named Involving citizen in textile recycling, focuses more on the citizens role, whereas this article looks at a different angle (Pichlova et al. 2021).

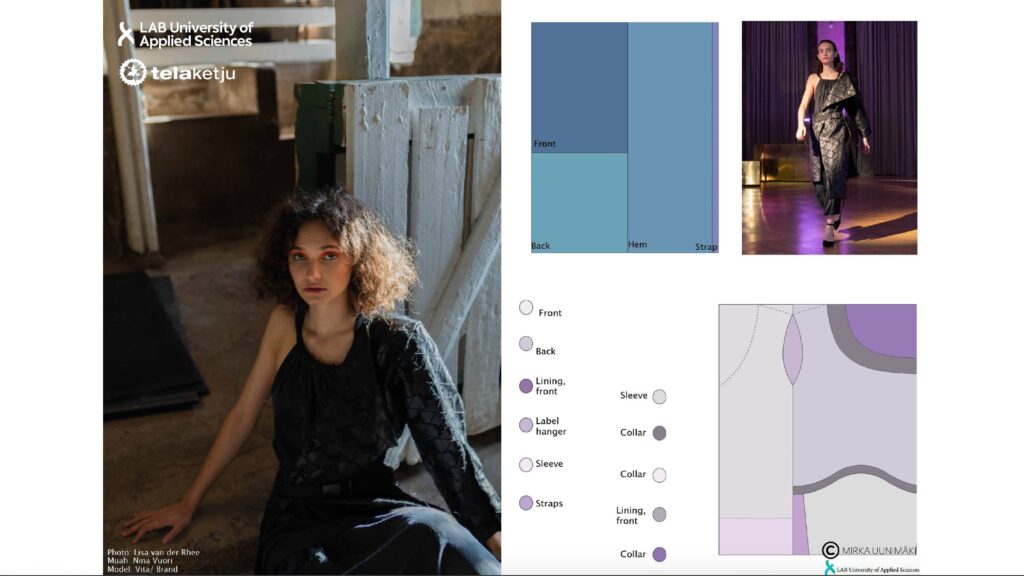

According to Annariina Ruokamo, RDI Specialist and Educator at LAB University of Applied Sciences, the circular fashion industry is one in which waste and pollution are designed out, products and materials are kept in use for as long as possible, and natural systems are regenerated. Although there is much room for improvement throughout the entire life cycle of the products, 80% of their environmental impacts can be taken into account during the design stage. Focusing on “needs not wants”, as well as use, repair, disassembly, recycling, and collection – these aspects must all be considered during the design process. (Ruokamo 2021.)

Image 1: Printscreen from a presentation of circular design examples. (Ruokamo 2021.)

Projects, such as CiLAB in Mechelen enable students, professionals and consumers to gain a better understanding of the issues at stake and change their personal and professional habits (CiLAB 2021). Public authorities can also help entrepreneurial designers such as Sandra Pasero (2021), and her brand Awahi, to develop their projects through incubator support, financial support, or public procurement.

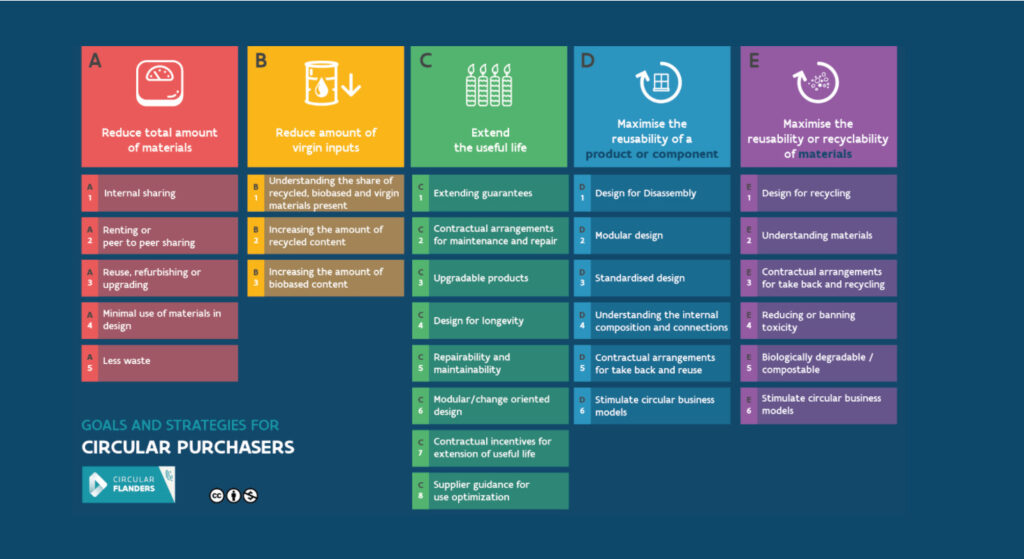

Public procurement makes sense

According to Sitra, public organisations use billions of euros every year, therefore they should accelerate the circular economy shift by procuring alternative products and services that are the most sustainable and effective from a societal perspective. This would boost the novel circular services and inspire citizens in adopting them as well. (Sitra 2019.)

According to the Harnessing Procurement to Deliver Circular Economy Benefits report, it is crucial to include existing initiatives to better define relevant regional goals and timeframes. Moreover, providing those collaborative frameworks will help stakeholders learn from each other, host pilot schemes, and monitor successes and barriers. (Pianoo 2017, 5.)

For instance, the Dutch Ministry of Defence set up requirement for procured towels and overalls, with at least 10% recycled post-consumer textile fibres. This resulted in savings of 15,252 kg of cotton, 68,880 kg of CO2, 23,520 MJ of energy, and over 233 million litres of water. (European Union 2017, 14.)

Image 2: The circular ambition chart is a tool helping organisations to get started with circular procurement. (Circular Flanders 2021.)

The European Commission defines Extended producer responsibility (EPR) as “an environmental policy approach in which a producer’s responsibility for a product is extended to the post-consumer stage of a product’s life cycle.” EPR helps to meet national an EU recycling and recover targets. (European Commission 2019.)

EPR aims at ensuring that producers contribute financially to the costs of waste management. It obliges producers to take operational or financial responsibility for the end-of-life phase of their products. EPRs then become an economic instrument to stimulate better design and reduce such costs. (Euratex 2019.)

Along with better collection systems and perception from the public, the report by WRAP (2017) notes that further research into textile recycling processes is necessary to offer a consistent alternative to newly produced fabrics. Mechanical systems for sorting and shredding need to be more financially attractive. Chemical processes such as dissolving, and purifying are still in their early stages. Moreover, there is still a work to do concerning quality standards, guarantees, and line optimization for different fibres and different end-use applications. (Wrap 2017.)

The Telaketju 2 project, presented by Kirsti Cura from LAB University of Applied Sciences, is an inspiring example that shows how to engage companies, scientists, and students in a collective effort in a shared ecosystem, to meet economic and legal demands. It involved hosting open online meetings and fostering international cooperation and was suggested and supported by Euratex. (Cura 2021.)

Conclusion

For the big transition towards sustainable and circular textiles, all players are needed on board in all levels of the textile’s life cycle. It is not only about discovering new sustainable alternatives and solutions, but also increasing consumer awareness and changing behaviour and consumption habits. This work should be backed up by policy and governance agenda.

The next two forthcoming articles direct attention to new circular textile business opportunities and legislation in partner regions.

References

CiLAB Collective. 2021. CiLAB Collective. [Cited 11 Apr 2021]. Available at: https://sites.google.com/view/cilab-collective

Circular Flanders. 2021. The circular ambition chart. [Cited 11 Apr 2021]. Available at: https://aankopen.vlaanderen-circulair.be/en/getting-started/the-ambition-map

Cura, K. 2021. LAB University of Applied Sciences: Telaketju network and actions. Presentation given at CECI Thematic Workshop on Textiles on 24 March 2021.

Euratex. 2019. EXTENDED PRODUCERS RESPONSIBILITY IN THE TEXTILE SECTOR. [Cited 06 Oct 2021]. Available at: https://euratex.eu/news/epr-in-the-textile-sector/

European Union. 2017. PUBLIC PROCUREMENT FOR A CIRCULAR ECONOMY Good practice and guidance. [Cited 28 Sep 2021]. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/pdf/Public_procurement_circular_economy_brochure.pdf

European Commission. 2019. Development of guidance on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). [Cited 06 Oct 2021]. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/archives/waste/eu_guidance/introduction.html

Interreg Europe. 2021a. Project Summary. CECI. [Cited 07 Oct 2021]. Available at: https://www.interregeurope.eu/ceci/

Interreg Europe. 2021b. Project good practices. CECI. [Cited 07 Oct 2021]. Available at: https://www.interregeurope.eu/ceci/good-practices/

One Planet Network. 2020. New Report Launched – Sustainability and Circularity in the Textile Value Chain. UNEP. [Cited 21 Oct 2021]. Available at: https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/new-report-launched-sustainability-and-circularity-textile-value-chain

Pasero, S. 2021. AWAHI: Clothes from pet-plastics. Presentation given at CECI Thematic Workshop on Textiles on 24 March 2021.

Pianoo. 2017. Harnessing procurement to deliver circular economy benefits. REBus. [Cited 23 Sep 2021]. Available at: https://www.pianoo.nl/sites/default/files/documents/documents/rebusharnessingprocurementtodelivercirculareconomybenefits-dec2017.pdf

Pichlova, A., Delaunay-Belleville, A., Villanen, M & Medkova, K. 2021. Involving citizen in textile recycling. LAB Pro. [Cited 25 Oct 2021]. Available at: https://www.labopen.fi/lab-pro/involving-citizen-in-textile-recycling/

Ruokamo, A. 2021. LAB University of Applied Sciences: Clothing Design for Circularity. Presentation given at CECI Thematic Workshop on Textiles on 24 March 2021.

SITRA. 2019. Public procurement to accelerate the circular economy. [Cited 7 Oct 2021]. Available at: https://www.sitra.fi/en/cases/public-procurement-accelerates-circular-economy/

Speranskaya, O., Caterbow, A., Vito A. & Buonsante, A. 2018. The Sustainability of Fashion: what role can consumers play?. Health and Environment Justice Support International. [Cited 21 Oct 2021]. Available at: https://hej-support.org/the-sustainability-of-fashion-what-role-can-consumers-play/

WRAP. 2017. WRAP 2017 Economic and Financial Sustainability Assessment of F2F Recycling. [Cited 07 Oct 2021]. Available at: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-04/F2F%20Closed%20Loop%20Recycling%20Report%202018.pdf

Authors

Barbora Pichlova works as a community-building expert at makesense and a CECI advising partner

Antoine Delaunay-Belleville works as circular economy specialist at makesense and a CECI advising partner

Marjut Villanen works as an RDI specialist at LAB University of Applied Sciences and is the CECI Project Manager

Katerina Medkova works as an RDI specialist at LAB University of Applied Sciences and is the CECI Communication Manager

Illustration: https://pxhere.com/fi/photo/1149845 (CC0)

Published 25.10.2021

Reference to this article

Pichlova, B., Delaunay-Belleville, A., Villanen, M. & Medkova, K. 2021. Sustainability all the way from design and public procurement into recycling. LAB Pro. [Cited and date of citation]. Available at: https://www.labopen.fi/lab-pro/sustainability-all-the-way-from-design-and-public-procurement-into-recycling/